It's Wednesday April 24, 2024

News From The Village Updated Almost Daily

Lots of boats come to Oriental, some tie up at the Town Dock for a night or two, others drop anchor in the harbor for a while. If you've spent any time on the water you know that every boat has a story. The Shipping News on TownDock.net brings you the stories of the boats that have visited recently.

February 15, 2013

The cutter “Ideath” was never supposed to have four gudgeons and pintles on her rudder. Like double the hinges on a door where half would do, they speak to extra heavy use. “I built her for sailing on a lake,” says owner Randy Mims. “I figured when I retired I would build the perfect offshore cruising sailboat.”He never imagined the gaff rigger would log enough coastal and offshore miles to stretch around the world.

The gaff cutter IdeathRandy MimsIf Randy had known from the start, he might have built Ideath’s rudder stronger. But how was he to know the boat he’d built to take him lake sailing would one day face the open ocean? Then it happened.

Ideath’s sturdily attached rudder. The gudgeons and pintles are secured, respectively, to hull and rudder. She has more of them then when she was launched.Randy was sailing Ideath far offshore, on passage. He noticed the rudder head making the wrong motion. Instead of turning smoothly on its axis, the top of the rudder was moving side to side. Randy quickly diagnosed the problem. The rudder was attached to the hull with hinge-like gudgeons and pintles. One of the gudgeons, the part attached to the vessel’s stern, was working loose. Randy was in danger of losing his rudder. A tow home was not an option. He had to come up with a solution. Fast.

With a length of rope, he stabilized the top of the rudder so it wouldn’t work side to side. With another, he frapped – that is, twisted around and around – extra lashings to the rudder.

Then he steered Ideath to shore.

Randy has always tried to be as self sufficient as possible. He sails with plenty of food, water and spares aboard. Luckily, he had the parts he needed on hand. Now he just had to figure out how to affect the repair.

Ideath’s cabin – port side. Built-in storage includes places to secure everything from a portable spotlight to a large fisherman’s anchor. The mesh bags store a series drogue that steadies the vessel under gale conditions. On the table is a copy of “Wooden Boat” magazine with featured Ideath in its January/February 2011 issue.Plastic bottles store Ideath’s water. Randy says if the vessel’s drinking water was contained in a single tank, a leak could leave him waterless at sea. Individual bottles minimize the chance of that happening. In addition to municipal water, he augments his supply with rain.Finances were tight. Instead of heading for a boatyard, where Ideath could be hauled ashore for repair, he would fix her in the water. He had an extra gudgeon on board, the part needed to fix the rudder. He just needed to find a place to repair his vessel.

He found what he was looking for in a patch of marsh abandoned by a marina developer. The developer had dredged a square opening in the swamp. Randy says it was, “ten feet deep all around”, plenty for Ideath’s 4-foot draft. The challenge now was to raise Ideath’s stern high enough to repair the rudder.

Years before, Randy had been given a supply of inner tubes. In an offshore emergency flooding, they were to be inflated to keep the vessel afloat. He dug a few from storage, tied them under Ideath’s stern and filled them with air. The vessel’s stern cleared the water. With a cordless drill, he drilled holes to attach the spare gudgeon. Rudder firmly re-attached, he resumed his voyaging under sail.

No, this wrestling with gudgeons and pintles offshore and in swamps never was part of the plan. Not for this boat, anyway.

[page]

Randy grew up in Greensboro, North Carolina. His youth was filled with small craft and he taught at Camp Seagull. He attended UNC Chapel, majored in sculpture and went to work in the audio field. In the years to come, he would work with bands from the Jackson Five to Alabama. In the early 1980s, he decided to build a boat. It would be a vessel of moderate size. Something to take him lake sailing. The “real” cruising boat – the steel one – he would build in his retirement.

Under a tarp in High Point he found the start of another man’s dream. The man had gotten as far as building the cement keel and mounting the frames and some stringers – the equivalent of a boat’s skeleton. Then he ran out of steam. The boat was the beginnings of a William D Jackson “Star-Lite” design.

Randy bought the boat, the vessel that, many years later, would become Ideath.

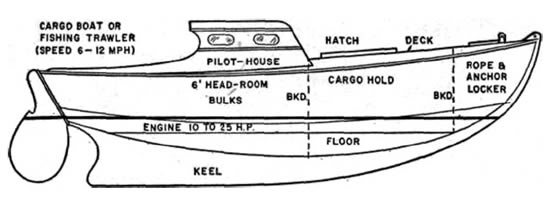

The “Star-Lite” design to which Ideath was builtThe 27 ½ foot Star-Lite was designed for back yard boat builders. The plans had originally run in “Science and Mechanics” magazine. The construction was simple. Something any motivated builder with access to plywood, lumber yard timber and simple tools could put together.

“I spent the next two years rebuilding what that last owner had done.” he says. Over time, he added plywood planking, decks and a cabin house. His materials came from salvage jobs and hardware stores. The Samson post – the heavy timber in the vessel’s bow used for securing lines and anchor rodes – came from a hundred year old house. Oak from a Lexington furniture plant became a bowsprit. The mast he built with 16-foot spruce planks purchased at Home Depot.

Here, the Sampson post holds a dock line. The anchor rode is secured to the deck with a length of line.Ideath’s rig looking aft. The green fabric covers the stay sail just aft the the bow. Randy says he noticed his local Home Depot occasionally substituted lighter spruce 2 by 6s instead of the usual, heavier southern yellow pine ones. He purchased the lighter wood and joined lengths of it to build his mast. He glued the spar up using the vacuum bag technique which ensures a tight fit. High wear parts of the mast are reinforced with fiberglass.When Randy learned it would cost $1,300 to buy the blocks to rig Ideath, he built his own. “A guy in church gave me a 2-inch brass bar and I thought ‘perfect, yeah!’” He cut the bar into slices and used the pieces to build his blocks.Ideath in her completed state. By the time Randy launched her in Savannah, he reckons he had about $6,000 tied up in her – along with “billions of hours.” The engine, added later, cost extra.On July 4, 1994, the boat that was only ever supposed to be for lake sailing was launched on Lake Hartwell.

At the time Randy was married. His wife chose to attend a yard sale instead of the boat’s launching. In hindsight, he says, it’s when he sensed the two were really growing apart.

The boat was launched as “Tradition”. The name didn’t stick.

Earlier, Randy had owned a farm. He says it was in the “back to the land hippy days” and he named his property after a house in Richard Brautigan’s novella “In Watermelon Sugar”. The structure’s name was “Ideath”. Randy liked the name so much, he passed it on to his farm and, in turn, his new boat.

When you see it, most people want to pronounce it “i – death”. That isn’t it. It is correctly pronounced “idea – th”.

Randy says his boat’s name unsettles some people because it raises the subject of mortality. He jokes the name might discourage pirates tempted to board his vessel, sending them off to look for a fancier yacht, a “goldplater”. He does carry sharper pirate repellent in the form of……roofing nails. Randy notes that Joshua Slocum, first man to sail alone around the world, scattered tacks on the decks of his “Spray”. They worked for Captain Slocum, but so far, Randy hasn’t used them. To blend in (if ever deployed), they are painted the same light blue as his deck.Ideath was a hit on Lake Hartwell. Especially the part about having no engine. Sailing with his son and friends, Randy learned to maneuver Ideath with sails and rudder. The sailing community took note. At the time, he was part of a yacht club. He says, “the club rules said that members were not allowed to enter the break water without their motor running.” A line was added to the rule. No members were allowed to sail into their berth – “except Randy.”

In 1999, he announced to his boss that he was going sailing. The kind that involved salt water. A long way from Ideath’s lake home. “He freaked out,” Randy says. “I told him, ‘don’t worry, it’ll take me a year to get ready.’” It did. Then a friend trailered Ideath from Lake Hartwell to Savannah, Georgia.

Randy’s cruising life had begun. His wife did not join him.

[page]

When he decided to go cruising, Randy says it troubled his father that he didn’t have a plan. He describes his dad as the sort of person who, “knows what shirt he’s going to wear next Wednesday.” To assure his dad he wouldn’t just be drifting about, he told Mims senior that he and Ideath’s quest would be to visit maritime museums. Mission defined, dad placated, he put to sea.

His shake down technique was simple. He would sail straight out into the ocean for a few days. Sometimes a week. Then turn around and come back. “After a week or two on the ocean, I would come back and anchor somewhere in a marsh.” Randy says. “I would sit there a few days and figure things out – what I’d learned at sea. I would replace what needed replacing. Restore things. Think about things.”

One of the things learned sailing offshore is that systems need to be simple and accessible. Here, Ideath’s galley.Rope ratlines make going aloft easier.During one stint of these ocean and marsh sessions, he spoke to almost no one for a month and a half. When he spoke with people again, in Fernandina Beach, Florida, he found he’d almost lost his voice.

Since those early ocean adventures, Randy’s cruising has fallen into a seasonal routine. His museum quest led him to the Apalachicola Maritime Museum on Florida’s west coast. He pays for his travels by working 9 months to year as a silversmith but also on boats. Often in Apalachicola. Sometimes at the museum. Then he goes sailing a year, as far North as Maine.

Once, he sailed nonstop and alone from from Apalachicola to Portland, Maine. It took 41 days.

Occasionally the ocean bites him.

Once Randy got caught in a Force 8 gale in the Gulf Mexico. To steady Ideath’s course, Randy shortened sail and sheeted the storm jib hard against the mast. To slow her progress, he deployed a 600 foot rope over the stern. One end of the rope was attached to each quarter of the transom, forming a large bight that trailed the vessel.

Things seemed well. Uncomfortable. But safe. These were the conditions he’d modified his vessel to weather.

Ideath’s main cabin. Randy says its narrowness is an asset. It means he can’t be thrown as far if he looses his grip in violent seas. The wood knees that join the cabin house to the deck serve two purposes. They reinforce the deck joint and give Randy “something good to hang on to” when the weather is rough.Forepeak starboard side. The helmet serves as protection under storm conditions. Randy has worn it twice in the past 10 years.Forepeak port side. Ideath’s reinforcing knees make an ideal place to store coiled lines. In heavy weather, the ports are covered with external plywood shutters for protection in case of a knock down.During the Gulf storm, the winds rose to over 30 knots. Ideath weaved her way among the 18 to 20 foot waves.

Randy wanted to photograph the violent seas. As he waited in the cockpit with his camera, hoping to catch the perfect wave, an extra large one slammed into Ideath. The crash threw him hard against the coaming and he came to rest face down in the cockpit. Then the pain hit.

Randy had a medical book aboard. Far in the gulf, in his wind thrown vessel, he diagnosed himself with broken ribs.

Lacking proper bandaging supplies, he resorted to some thin tape he found aboard. That was enough to make “about two turns” around his chest. So he dug into Ideath’s sail repair kit. “I took some of that wide sail tape and wrapped it around and around my chest. There was so much of that tape on me it looked like I was wearing a bullet proof vest.”

Then he started the long sail to shore.

The winds dropped. His injuries weren’t improving. With his torso seized in tape and pain he had to figure out how to operate Ideath’s sails, winches and lines. In the end he settled for a hand to mouth arrangement.

“I pulled with my right arm and tailed with my teeth.” he says. Four days later, he arrived in Panama City. The doctor who treated him, Randy says, told him, “we haven’t tapped up ribs for years!”

It didn’t matter. He and Ideath had survived their test at sea.

[page]

Randy considers Ideath a four knot boat. That means, on long passages, instead of outrunning foul weather, she must endure it. In her lake sailing days, Ideath’s main cabin took up most of the interior. For safety at sea, Randy divided it into two compartments.

To keep the cabin from flooding in case the hull was punctured, Randy installed a watertight bulkhead just aft of the mast. An oval opening in the bulkhead allows passage from the main cabin to the forepeak. Nights offshore, Randy closes this opening with a watertight hatch. If the hull is breached, the bulkhead should keep water from flooding the entire vessel.

Looking through the watertight bulkhead from forepeak in to the main cabin.He also designed and fitted a watertight companion way hatch. Only twice, when the seas ran taller than 15 feet, has he deployed it. Somewhere along the way, he installed an inboard engine.

The watertight companionway hatch stored under the cabin table. Coiled in mesh bags next to the hatch is a series drogue. The drogue, deployed over the vessel’s stern, slows the vessel in storm conditions. Randy hasn’t needed it yet.Though these improvement might suggest a confrontational relationship with the sea, Randy sees it otherwise.

He speaks of his days and weeks offshore in more spiritual than technical terms. Out on the open ocean, he says, “after 9 or 10 days, you’re in the rhythm of how the universe works. How it’s all connected. You don’t get that serenity until you’ve been out 8 to 9 days. At least.”

It’s only then that his mind grasps the enormity of the universe. The simplicity of life away from land where all that really counts is flowing past Ideath’s hull and rigging– the waves, the moon and the sky. And the stars. Especially the stars. They’re “amazing” far out at sea, amplified by a clear mind. Undiminished by light pollution.

Randy tidying Ideath at the Town Dock. He stays on top of the painting and varnishing as best he can, saying if he does some each year, taking care of a wooden boat isn’t too hard. He doesn’t go for a fancy finish, saying his vessel, “makes no pretense of being a yacht. It’s a boat.”It’s been 30 years since Randy discovered Ideath’s skeleton under a tarp in High Point. He’s 64 now. Together, they’ve sailed 23,000 coastal and ocean miles. Out of mind are thoughts of building the perfect steel offshore sailboat. Ideath, with her plywood hull, inner tube flotation and home made mast, will take him anywhere he wants to go.

Randy departed Oriental without saying where he was going. He just told one of his visitors, “time and tide wait for no one” and left. He dreams of sailing to Norway.