It's Thursday April 18, 2024

News From The Village Updated Almost Daily

Lots of boats come to Oriental, some tie up at the Town Dock for a night or two, others drop anchor in the harbor for a while. If you've spent any time on the water you know that every boat has a story. The Shipping News on TownDock.net brings you the stories of the boats that have visited recently.

August 10, 2011

One recent evening, just before sundown, a battleship-gray vessel steamed past the Oriental anchorage, motored under the bridge and dropped anchor at the mouth of Greens Creek. The vessel’s plumb destroyer bow and ash colored hull seemed out of place in North Carolina’s sailing capital. The vessel looked too purposeful to be merely a pleasure boat – too angular, too metallic. It had onlookers wondering. Was this a navy vessel, perhaps from a far off country?No. It was Steve and Linda Dashew aboard their 83-foot vessel “Wind Horse”.

Wind Horse anchored in Greens Creek. To the casual observer, Wind Horse looks military. “We are often mistaken for the Navy,” Linda says.Steve and Linda DashewTo understand Wind Horse and her unconventional looks, one has to look back into Steve and Linda’s sailing past – about half a century’s worth.

In the 1960s, Steve set the world speed sailing record aboard his D-Class catamaran “Beowulf”. Later, the couple sailed around the world in the “Intermezzo II”, their Columbia 50. Over the years, though, they never quite found the boat that met their cruising needs. So they designed and built the Deerfoot and Sundeer line of sailboats. Long and narrow, the premise behind these 60 and 70 foot boats was that a couple could sail them offshore in comfort and safety without additional crew.

“Beowulf”, the Dashew’s previous 78-foot sailboat. On passage, Steve and Linda were often the boat’s sole crew. (Steve and Linda Dashew photo)Not only did they design and build these boats, they sailed them. Lots. Over the years, the couple racked up tens of thousands of offshore miles. Fast passage makers, these vessels are known to sail up to 300 miles per day while most sailors settled for half that. Steve says this allowed the boats and their crews to minimize time, and therefore poor weather, offshore. Steve and Linda chronicled these experiences in books such as “Surviving the Storm”, “Offshore Cruising Encyclopedia” and “Mariner’s Weather Handbook”.

In time, though, Steve discovered a change that might not be as easily skirted or outrun. It wasn’t a meteorological storm. It was, Steve says, the march of time. Hauling and lowering sails on passage, day and night, in weather good and poor, was not as easy as it once was. So he and Linda decided on a life course correction. Not content to stow the anchor, they did what many diehard sailors would consider treason. They took up powerboating.

[page]

The trouble was, Steve and Linda couldn’t find a long range powerboat that suited their primary interest – voyaging offshore in safety and comfort. So, just as they’d overcome the challenge of finding a suitable sailboat, Steve says they “designed a boat to our own purposes.”

The hardest part, Steve says “was getting my head around it that I was designing a powerboat.” Once he managed that, he says, he could move ahead. The new vessel had to “combine heavy weather ability with a comfort function.” And therein lies the answer to Wind Horse’s non standard look. On the outside she’s pure function. Inside, comfort gets the nod. The result is an unconventional appearance not often associated with pleasure boats. Wind Horse is the type of boat that leaves some people wondering if they’re looking at a flush deck, homebuilt minesweeper.

Wind Horse as viewed from aftLong and narrow, Wind Horse is 83 feet long and 19 feet wide. This maximizes speed potential and minimizes fuel consumption. Cruising at 11 knots, she can easily cover 250 miles per day.Wind Horse viewed from the bowSteve built Wind Horse of aluminum. Though strong and light, it’s a hard material for paint to adhere to. So Steve left all exterior surfaces bare, preferring to let the raw aluminum oxidize to a flat, cinderblock -shade of gray. Considered unsightly by some boaters, he soon warmed to the “functionality of non-paint aluminum”, saying he “got used to the bare finish in a day or two.”

The hull features a double bottom and watertight bulkheads. The double bottom serves as tankage and flotation. Should the hull be punctured, chances are good a second layer of “hull”, in the form of a tank, would prevent flooding. If Wind Horse were to puncture a single hulled section of her plating, the watertight bulkheads should limit flooding to individual compartments that can be sealed off.

Step lively: one of the few drawbacks of a bare aluminum finish is heat. Though heavily insulated, Wind Horse’s decks get hot. That means, on sunny summer days, Linda says “you better walk fast” – or put on shoes.While Wind Horse has air conditioning, Steve and Linda have taken steps to minimize its use. Here, stowable fabric awning shade the pilot house and keep the decks cool.So how has Wind Horse worked out for them? Both agree she’s allowed them to do things they couldn’t have done aboard their previous sailboats.

Like visit Greens Creek in Oriental.

The sailboats Steve and Linda voyaged aboard for so many years relied on tall masts and deep drafts for stability and speed. Their 78-foot long Beowulf drew almost 8 feet of water and sported a spar that posed challenges at bridges. That meant while she could cross oceans in record time, cruising much of Intracoastal Waterway’s shoal waters was off limits for draft and clearance reasons.

The mastless Wind Horse, by comparison, can slip under most bridges and explore relatively skinny waters. She draws only 5 feet. This allowed Steve and Linda, who were on their way to Norfolk, to steam under the Oriental bridge and drop their anchor at the mouth of Greens Creek.

Not that Wind Horse is limited to coastal motoring. With two diesel engines and a range of over 5,000 miles, Wind Horse could theoretically, if motored conservatively, travel a quarter of the way around the world without refueling. A few years ago, Steve and Linda traveled up the East Coast without ever coming near Oriental. They sailed from the Bahamas straight to Greenland. Another time, Linda says they traveled “farther north than we ever went in a sailboat – to Svalbard.” Svalbard lies North of the Arctic Circle, about halfway between the North Pole and mainland Norway.

[page]

For as functionally metallic as she is on the outside, Wind Horse is comfortable and high tech within. Forward, to maximize natural ventilation, is the master stateroom. Aft are two guest cabins and the engine room. Amidships is dominated by a glass walled pilot house.

Inside the pilot house (Steve and Linda Dashew photo)The master stateroom: its forward location, and massive opening hatches, maximize natural air circulation at anchor.At the front of the pilothouse is the steering station. Here an array of radar, computer screens, digital readouts inform Steve and Linda everything about Wind Horse’s operation. Speed over ground, magnetic course, port engine temperature, starboard engine oil pressure. Everything a high tech boater would want to know.

The helmAnd herein lies the potential problem. While advances in technology and communications make it easier than ever for people to cast off their lines and put to sea, there’s a downside. “What’s been lost” says Steve, “is general seamanship.”

Enter the logbook.

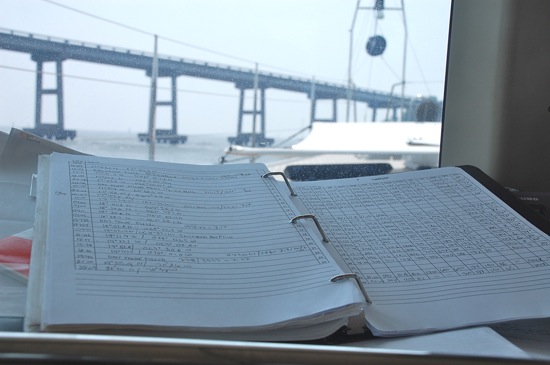

Off to the side of all the instruments dominating Wind Horse’s helm is a binder. Not a expensive leather covered logbook but a plastic D-ring binder filled with pages headed “COG”, “SOG” and “RPM”. It’s here where Steve and Linda keep a traditional written log while on passage. Generally once an hour, more or less often as needed, they record Wind Horse’s vitals: Course over ground, Speed over ground, Revolutions per minute.

Wind Horse’s log book. A black anchor ball, required of anchored vessels, is visible through the pilot house window.Deeper in Wind Horse’s interior, filed away for easy retrieval, is a collection of paper charts. While not fancy, all this paper serves as a simple backup in case of electrical failure. Or, as Steve only half jokingly notes, “we get hit by lightning….” Wind Horse also has a back up water supply organized. In rainy weather, deck water can be diverted to the main water tanks.

The circular fitting is a deck fill along one of Wind Horse’s gunwals. During rain showers, it can be used to divert rainwater into Wind Horse’s water tank.Many sailors dread the thought of changing from sail to power, seeing the transition as a compromise, a sell out. What do Steve and Linda think of swapping mast and sail for engine?

They’ve had 7 years to ponder it. Since launching Wind Horse in New Zealand, they’ve put over 50,000 miles under the keel. That’s the equivalent of traveling twice around the world – all without having to worry about checking rigging, stepping masts or hauling down sails in poor weather.

At a certain age, they’ve learned, that definitely has its advantages. They now both agree that voyaging under power “is just easier” than sailing. Even if doing it on their terms means showing up in Greenland on a vessel that’s been mistaken for a dredge.

Wind Horse anchored in the night.From Oriental, Steve and Linda plan to head to Norfolk, and then north on a route TBD.